A Brief History of Pittsburgh’s Bathhouses

An entry pass to Kalson’s shvitz, courtesy of the Kalson Family Papers and Photographs at the Detre Library and Archives.

The Original Bath House

As some readers may already know, Pittsburgh has a long and varied history of public bathing establishments dating back to at least 1834 when John B. Vashon opened the first public bath house, The City Baths, on Third Street, between Market and Ferry. (the sweat bathing practices of Native American peoples of the region will be the subject of a subsequent newsletter)

Among the amenities of the City Baths were included “Warm, Cold and Shower Baths” with water supplied by one of the city’s rivers (or “La Belle Rivière,” as it was affectionately called in one ad for the Baths), and over a dozen individual bathing rooms, all illuminated by gas lights. This would have been a major upgrade for many of the Baths’ patrons, whose alternatives included bathing in the city’s rivers—a main option for bathing up until 1895, when nude river bathing was outlawed between sunrise and 8:30 p.m.

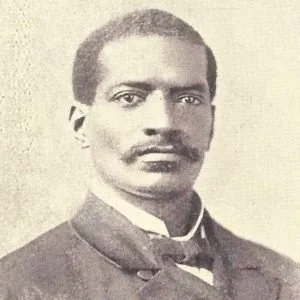

In addition to his role as bathhouse purveyor, John B. Vashon was a prominent abolitionist and the city’s wealthiest black businessman, and was known for mediating between the interests of the city’s black and white residents, many of whom intermingled at the bathhouse. One can easily imagine the City Baths serving as a sort of abolitionist salon with lengthy debates about slavery taking place in the building’s relaxed atmosphere. But Vashon, and by extension the Baths, were not content to merely facilitate discussion of ending slavery: the building’s basement served as a stop on the Underground Railroad for slaves escaping North.

John B. Vashon

1860-1894

The late 1800s in Pittsburgh were defined by a radical shift in the material conditions experienced by the population, alongside changes in social mores and official opinion. Rapid industrialization led to a concentration of people and pathogens at the same time when the public’s access to clean, untainted water was drastically diminished. The days of the “La Belle Riviere” were gone and Pittsburgh was now known as “Hell with the lid off,” referring to the heavy smoke that clogged pores and congested lungs. Coupled with developments in the medical field and shifting opinions on Russian and Turkish bathing traditions, a new type of health conscious bathhouse had begun to emerge all across western Europe and North America, and Pittsburgh was no exception.

Bathing services were often the purview of barbers, medical doctors, and at least one “cupper and leacher” in this time period. While some of the methods used by the practitioners in these health spas, such as steam bathing, are familiar to us now, others, like “electric baths” will likely give the reader pause. These were used to treat an array of ailments, from catarrh, inflammation, bronchitis, rheumatism, and “diseases of the rectum.”

An advertisements in the Pittsburgh Daily Post from June 9 1890.

”No dirty river water to bathe in”—a far cry from a 1838 advert for the City Baths trumpeting bath water from “La Belle Rivière.”

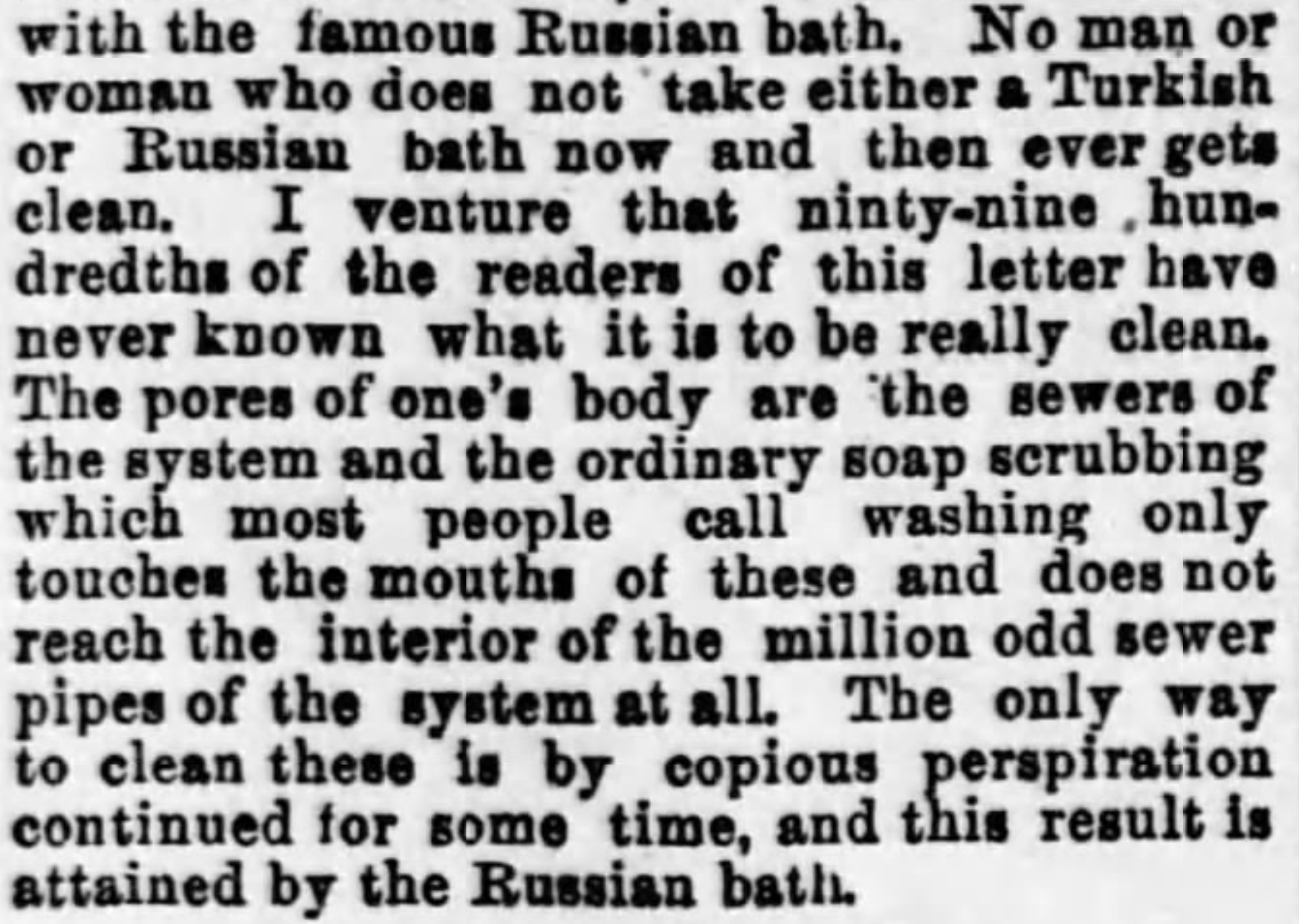

A traveler’s account in the August 21, 1892 edition of the Pittsburg Dispatch (not a typo, as Pittsburgh briefly dropped the “h” in the late 1800s) illustrates the changing attitudes towards the Russian “banya” or steam bath.

The choice of metaphor here, of pores to a sewer system, reflects an increasingly mechanical view of the human body, as well as gesturing toward the relationship between the modern subject and their rapidly changing urban environment.

Ad in the Pittsburgh Press, June 9, 1890.

Long before podcasts and Instagram there were health influencers.

The coarse exclusivity of the Natatorium—“objectionable persons rigidly excluded”—would sit in striking contrast to the populism of the coming era of the Progressive public bath house.

1894-1950

In 1894, in response to the intensifying public health emergency, Andrew Carnegie began to provide bathing facilities in his libraries, initially for steel workers and later for entire communities surrounding his mills. Soon, other industrial tycoons, and the civic organizations they funded, began to build public bathhouses. The first of these, the People’s Baths, opened in 1897 at the corner of 16th Street and Penn Avenue in the Strip, and included 32 marble showers and two tubs. Showers cost a nickel and included soap and a towel. The People’s Baths served 846,539 people before moving to 1908 Penn Avenue in 1910.

Public bath houses proliferated across the city during the Progressive era, including the Public Wash House and Bath at 3445 Butler Street, the Soho Bath House at 2408-2410 Fifth Avenue, and the Oliver Bath House, an indoor pool still operational today at 38 10th Street on the South Side.

An illustration of the baths inside the People’s Baths from the November 20, 1898 edition of the The Pittsburgh Press (notice, the “h” is back!).

This period also coincided with increasing immigration from eastern Europe, and with the new arrivals came the introduction of the Russian-Jewish shvitz to the lower Hill District, including several establishments on Epiphany Street.

While there had been “Russian-style” bathing prior (within the context of medical spas like the Natatorium on Duquesne Way), the shvitz represented something entirely new in Pittsburgh: an authentic reproduction of a centuries old steam bathing tradition, complete with its own rituals, beliefs and idioms. These new establishments served as a home for the common Jewish laborer and well-to-do merchant alike, and boasted a proficiency with oak branches (or venik, in Russian) that was something new in the burgh.

Aside from a place to get clean, the shvitz also served as an informal space for political discussion and debate. On Saturdays especially, while religious Jews were in synagogue, the bathhouse was patronized by the Jewish left—socialists, communists, and union card holders of all strips. At Daniel’s Bath House (1306 Epiphany St.), the hot room was divided on Saturday afternoons between the “linka” and “rechta,” or left and right, referring to where the communists and socialists sat, respectively. As Hyman Richman recalled from these Saturday afternoons at Daniel’s, “During the week they would do research, everything else, and then they would have these unending disputations that would go on in the middle aisle… I had no idea of the value of these bath sessions until I started college.”

Between world wars the shvitz began to attract customers from beyond its initial, Ashkenazi clientele. Soon, a practice once regarded as an anachronism of Russian peasants, became fashionable among Pittsburgh’s political class, nightlife scenesters, sports celebrities, numbers runners, opera singers and power brokers of all sorts. As one article described Kalson’s shvitz (1313 Epiphany St.) in 1933,

“In the steam room, where four wide steps lead to increasing temperatures–the higher you go, the hotter it gets—all the gossip of the day is passed between turns at the oak leaves. And in the Russian bathhouse, it is said, more racing pools have been cut up, and more big money coups plotted among the burgh’s professional sportsmen, than in any rendezvous in Pittsburgh. A busy night presents an interesting “Who’s Who” literally in the flesh.”

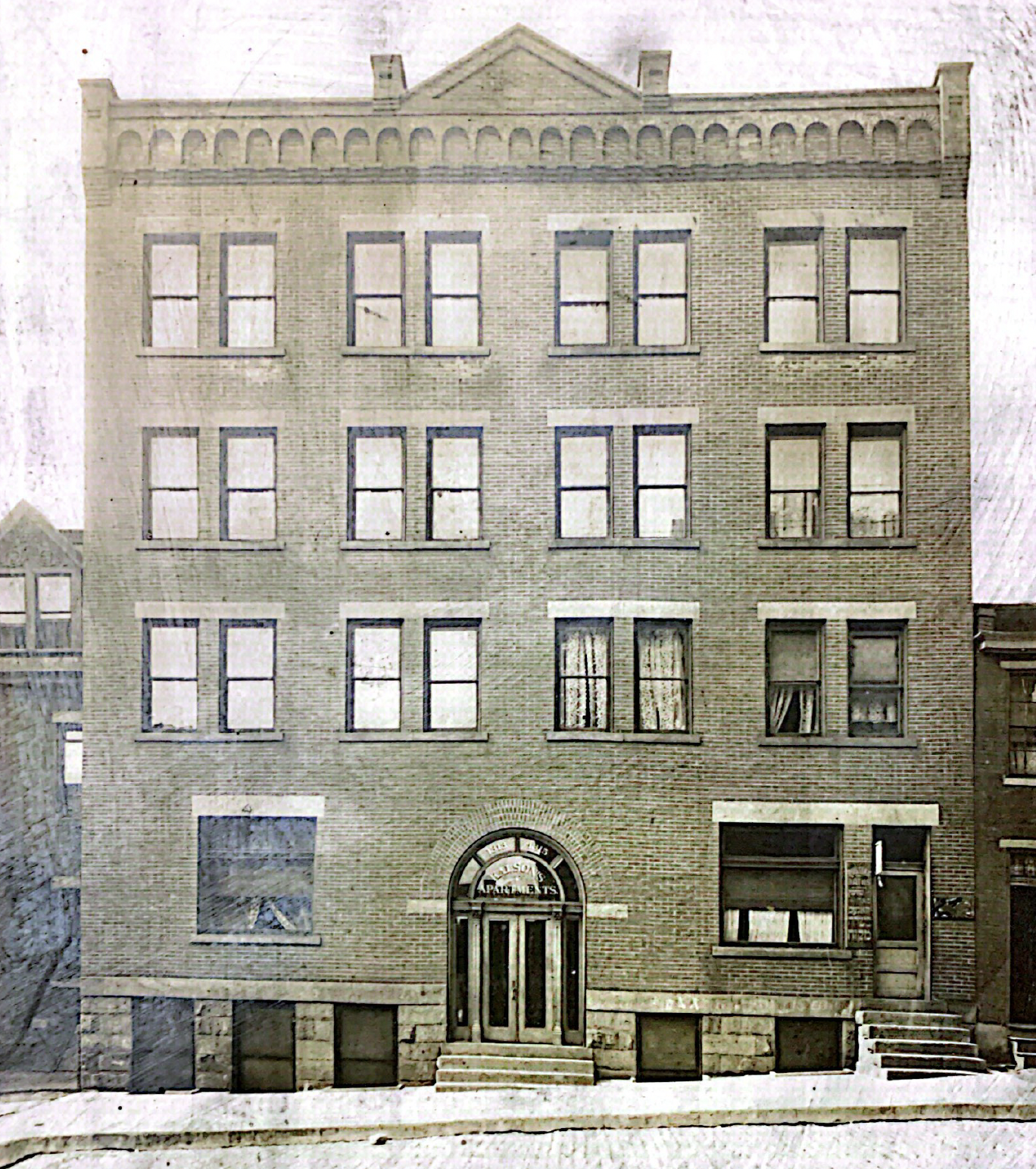

The Kalson apartment building. Notice the sign in Yiddish in the lower right—this was the entryway to the shvitz.

Daniel Anolik of Daniel’s Bath House and his “enforcers” in the lower Hill. Photo courtesy of the Anolik family. Like their Epiphany Street rival, Kalson’s, Daniel’s Bath House was demolished along with the rest of the lower Hill during the “Pittsburgh Renaissance”, or the mid-century phase of urban redevelopment that created the Civic Arena.

1950-2001

The city’s appetite for public bathing exploded between the 1930s and 50s, with a proliferation of Turkish baths, “Egyptian Natural Herb Baths”, Health Institutes and Ritulariams, right up until modern indoor plumbing, white flight, and a culture of consumer-driven individualism sucked the wind out of their sails. In 1950 there were 14 public bathhouses listed in the city’s directory; by 1960 there were six and by 1970 there were just three. While the 1950s and 60s represented a turn away from public bathing for most Pittsburghers, for the city’s gay community the bath house scene was just getting started.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette September 27, 1979.

The history of gay bathhouses predates the twentieth century, and there’s no reason to believe that gay men and women were not finding one another in Pittsburgh’s bathhouses long before mid-century. However, it was only in the period that the city’s bathhouses began to be known as specifically catering to this demographic.

In 1979 there were three gay bathhouses (and probably the only bathhouses in the city period): Arena Baths (2025 Forbes Ave.), Club Baths (824 Fifth Ave.), and Schume’s Liberty Baths (937 Liberty Ave.). (Schume’s had been around since at least 1930, and it’s not clear when it became a predominantly gay establishment, assuming it wasn’t set up with that intention) For the gay community, the baths were not merely a site for sexual encounters, but also a gathering space for community. One informant told Bad News that the bathhouse scene was sometimes affectionately known as the “gay country club.”

As with so many aspects of gay life in the 1980s, the horrors of the AIDs epidemic deeply transformed bathhouse culture, as most were too scared to patronize the baths. By 2000, the only bathhouse listed in the yellow pages was the Arena Health Club. That changed in 2001 when Club Pittsburgh came into existence, a gay bathhouse in the Strip District that is thriving to this day.

Looking in the other Direction

Today, most people bathe at home. However, there may be more to a bathhouse than getting clean. Throughout their history, Pittsburgh’s bathhouses have served as gathering spaces for communities, sites of political and social discourse, cultural centers, public health assets, and portals to freedom for slaves escaping north.

There is something special about a sauna. Perhaps it’s the ability to meet your neighbors in relaxation. Or the mingling of high ideals with bodily sensation. Or the inherent democracy of sharing steam. In any event, there are signs of a bathhouse revival— a growing interest in traditional bathing practices and a proliferation of public bathing spaces in other cities. If these signs are more than just static, “A Brief History of Pittsburgh’s Bathhouses” may prove merely the prologue.

The only bath house in Bloomfield, at least for now…